Some of my international friends have asked what the recent death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia means for America, for our process, and for the election. I couldn’t fit it into a tweet, so I thought I’d share my understanding and opinions here. I don’t have any great insights or expertise, but I hope this is useful for those who haven’t delved into the peculiarities of US government and law.

The death of Justice Scalia leaves a seat open in the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), the third branch of government (the Judicial branch); the other two branches are Congress (the Legislative branch, comprised of the House and Senate), and the Presidency (the Executive branch).

The Supreme Court has 9 Justices, appointed for life. This means that whomever is appointed as a replacement for Scalia will likely affect the tone of American justice for decades after the President who appointed them has left. Scalia was appointed in 1986, by President Reagan, and has been a consistently conservative voice for 30 years, frequently writing scathing and sarcastic dissenting opinions (“minority reportsâ€) for decisions he did not agree with, including the legalization of same-sex marriage, Obamacare, women’s rights to abortion, civil rights, and many other progressive issues. Though he was intelligent, witty, and well-versed in the law, he was not kind in his judgments.

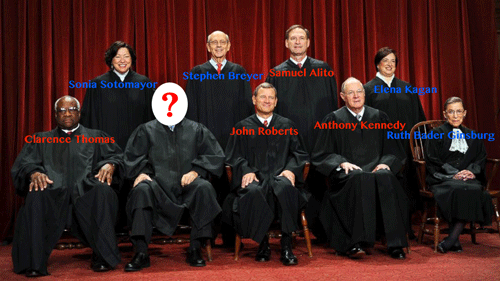

When Scalia was alive, the Supreme Court was almost evenly split between conservatives and progressives, with Chief Justice John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Antonin Scalia on the strongly conservative side, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor on the moderate to strongly progressive side; the deciding vote has usually been the generally fair-minded, moderately conservative Anthony Kennedy. The death of Justice Scalia changes that balance. It’s expected that President Obama would nominate a progressive as Scalia’s replacement, and though he hasn’t yet named a candidate, conservative politicians have already attempted to block Obama’s appointment (in the true spirit of ♫whatever it is, I’m against it♫ ), leaving it to the next President to decide.

It’s the duty and right of the sitting President to name replacement nominees to the Supreme Court (and Obama does intend to do so), and the duty and right of the Senate (not all of Congress) to approve these nominations. This has been highly politicized in the past few years, with more and more attempts by both conservatives and (to a lesser extent) progressives to block Supreme Court appointments, drawing out the debate, so there’s some wisdom in nominating a moderate Justice, in hopes of a speedy and non-contentious approval by the Senate. Notably, the nominee doesn’t have to be a current judge, or even a lawyer, but in reality, the Senate would be unlikely to approve anyone who isn’t a law professional (with good reason).

The nominee must get a simple majority in the Senate; currently, with 2 Senators from each of the 50 States, that means 51 approval votes.

The Republicans control the Senate, with 54 senators; the Democrats have only 44 senators; Independents make up the balance, with 2 senators (Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Angus King of Maine), who typically vote with the Democrats. While there are a few conservative Democratic senators, it’s likely that all Democratic and Independent senators will vote to appoint Obama’s nominee, whomever that might be. That’s only 46 votes, meaning at least 4 Republican senators will need to cross party lines to vote for the appointee… in an election year. That could be a tough sell for Obama.

But Obama has 342 days left in office, and the longest Supreme Court confirmation process, from nomination to resolution, was 125 days, back in 1916, when nominee Louis Brandeis “frightened the Establishment†by being “a militant crusader for social justiceâ€. (Thanks, Rachel Schnepper!) In today’s sharply divided and fractured political system, I expect that we will set a new record for how long it takes to confirm a Supreme Court Justice, if it happens in the Obama administration at all.

If you did the math, you’ll have noticed that 46 + 4 = 50, not 51; luckily, if there’s a split vote in the Senate, the Vice President casts the deciding vote, and Joe Biden is closely aligned with President Obama.

If Obama can’t get the votes he needs for his nominee (a real possibility), he could wait until Congress adjourns for the year, and make a recess appointment, meaning a judicial selection while Congress is not in session; but this appointment would be temporary, less than 2 years, and the next President would certainly be the one to make the permanent appointment.

I’m reasonably confident (though not certain) that the next Supreme Court Justice will be a progressive, and will be appointed by President Obama, not the next President. But that wouldn’t mean that the implications of this for the 2016 Presidential election are any less notable! Other Justices (including the beloved Notorious RBG and “Swing Vote†Kennedy) may step down or even die during the term of the next President, meaning that the balance might shift yet again. We can’t ignore the fact that Bernie Sanders, a sitting Independent senator, will have a vote in the current Supreme Court nomination, while Hillary won’t, which will likely raise Bernie’s profile (for good or ill). And while the nomination process is underway, all the candidates will talk about who they’d appoint to the Supreme Court (keeping in mind that Obama probably doesn’t want the job), though I dearly hope they don’t get the chance. Finally, there’s the tiny chance that in a close race, the Supreme Court may decide who the next President is…

The Impact of the Supreme Court

It’s easy to underestimate the power the Supreme Court has on America’s domestic policy, and on people’s lives. What is legal or not is often (perhaps usually) decided not by Congress (the Legislative branch, which drafts, proposes, and votes on new federal laws) or the President (the Executive branch, which approves, implements, enforces, and administers those federal laws), but by the Supreme Court (the Judicial branch, which decides if federal laws adhere to the Constitution, and which acts as the final say on the application of federal laws, and on how state laws are affected by federal laws and the Constitution).

Some landmark policies that the average person associates generally with the US government were specifically decided by the Supreme Court:

- the legality of a woman’s right to abortion (in the famous court case Roe v Wade)

- whether states had the right to keep their schools segregated between black students and white students (and much earlier, whether African American slaves were entitled to citizenship)

- whether same-sex couples can get married (and earlier, whether interracial couples could get married)

- whether there is any limit on how much money a corporation or union can spend in elections (under the aegis of free speech)

- the legality of some aspects of Obamacare (aka the Affordable Care Act), which determined if the law as a whole could be implemented

- whether Florida could recount the ballots in the contested 2000 election between George Bush and Al Gore (though this is a rare instance… that usually doesn’t happen)

Some of these are issues that could have specific federal laws about them, but which Congress did not address. For example, Congress has never made a federal law that makes same-sex marriage legal, and it probably would have been decades before that would ever have happened, if it ever did (politicians typically play it safe, because they have to try to get re-elected); but based on the Supreme Court’s hearing of lower (state and district) courts’ rulings on state laws to determine if state laws were legal through the lens of the federal Constitution, and on the Supreme Court’s decision around some federal laws, it became legal for same-sex couples to get married. Congress could still make a law on this, one way or another, to settle details or try to overturn the Supreme Court’s decision (for example, by changing the Constitution itself), but for the foreseeable future, the Supreme court made same-sex marriage legal in every state of the Union, and has all the federal benefits of marriage.

The Supreme Court decides which cases it will try. On average, SCOTUS tries 60-75 oral arguments (what we think of as a court case) per year, and reviews another 50-60 more cases on paper.

Every year, tens of millions of civil and criminal court cases are tried in US state courts; hundreds of thousands of those decisions are appealed to a higher state court; tens of thousands of those are appealed to a federal district court, if the matter is applicable to federal law rather than state law, and district courts are further organized into 11 federal circuits; thousands of these cases are appealed to the Supreme Court, of which they accept a mere 1–2%. In addition, there are court cases of major federal or interstate crimes, and cases of disputes between state governments or between a state government and the federal government, or maritime laws where no state has jurisdiction, or cases of bankruptcy or ambassadorial issues.

So, the chance that the Supreme Court will hear any particular case is very slim, and is typically only the most important cases, but when they do rule on a case, it sets the precedent for the rest of the country, at a state and federal level, and is rarely overturned.

Scalia’s Legacy

While it’s not polite to speak ill of the dead, and while I can mourn Scalia’s death as a person, I’ve long held a very low opinion of him, and I admit that I’m glad of any opportunity to shift the character of the Supreme Court to a more progressive, compassionate, and modern constituency.

Many have painted Scalia as a patriot who’s made America better; here’s my dissenting opinion.

Scalia was clever, and I think it’s even more important for clever people to also strive to be good people; even more so if they are in a position of power. He may have been a good person to his friends and family, but he did not carry that over into how he served this country.

His writings struck me as insincere, and his claim to adhere to “Constitutional originalism†was belied by his whimsical interpretations of the US Constitution, such as his very modern stance that the 2nd Amendment ensured private ownership of guns, rather than the original emphasis on militias for national defense, and the absurd notion that “The Constitution is not a living documentâ€, when the Constitution itself defines how to amend it.

And while he’s perhaps most famous for his dissenting opinions, it’s his majority rulings that have caused the most damage to America and Americans. And even beyond that, he’s used his Judicial authority to step into decisions on lower courts. For example, in 2000’s Presidential election, it was Scalia who personally intervened in the Florida court decision to halt the recount, and later the Supreme Court ruled not to let the votes be recounted, handing the election to George W. Bush.

Beyond his own rulings, his influence and legacy is in giving voice, authority, and credibility to a radical conservatism that influenced a generation of legal thought, carried on in Alito and Roberts, which holds that interpreting the text of the law is more important than the applicability to modern society and technology. In other words, it claims that trying to imagine (in a ridiculous fantasy) the opinions of a person living over two centuries ago, when this country was yet unformed, is more relevant than a view informed by the country as it has since developed. Generously, this is truly “conservativeâ€, preserving the prejudices and ignorance of bygone eras along with any wisdom; more pointedly, this was a convenient way to appear impartial while twisting the result to his own backwards ideological view.

Scalia’s rulings were often specious and inhumane, mere clever arguments based on selective interpretation of the wording of laws and the Constitution rather than attempts at applying justice. In dissenting on a ruling for reopening a death-penalty case, where most of the original witnesses had recanted their testimonies, Scalia said, “Mere factual innocence is no reason not to carry out a death sentence properly reached.†For Scalia, it seems, the law was not a way to achieve social or personal fairness, but a pro-forma game whose rules were both strict and meaningless.

It’s hard to imagine someone as retrograde as Scalia getting nominated or confirmed, so I’m hopeful that we’ll have a more reasonable, just, and progressive Supreme Court in the next few months. This is how the Founding Fathers wanted this country to work… with each generation forging its own vision of a more perfect union, renewing the government to meet their own needs and desires, with the consistent thread of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And, in the end, justice.

This is a very clear exposition, especially for those of us who are not close to American politics. The name of Scalia sounded familiar to me, and I think I even knew he was a conservative judge. But your overview was useful.

Cheers, Doug 🙂

(BTW, did you see http://blog.dilbert.com/post/139421165806/scalia-and-the-pillow ? 🙂 I don’t take it seriously — Scott Adams always writes that way… But I thought it was clever.)